Though not widely known after it was composed in 1674, John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” grew in popularity to be hailed as the greatest epic poem of the English language. Rarely read today, it would have been read by nearly all educated Englishmen during the lifetime of William Blake. Blake made his name as an illustrator of “Paradise Lost”, Dante’s “Divine Comedy”, and the Bible, in addition to his own books of poetry.

Though not widely known after it was composed in 1674, John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” grew in popularity to be hailed as the greatest epic poem of the English language. Rarely read today, it would have been read by nearly all educated Englishmen during the lifetime of William Blake. Blake made his name as an illustrator of “Paradise Lost”, Dante’s “Divine Comedy”, and the Bible, in addition to his own books of poetry.

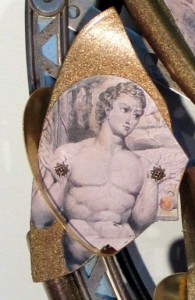

The energy and geometry of Blake’s illustrations—especially his use of the serpentine line, defined by Hogarth as the “Line of Beauty”, and used commonly by artists of the period as a device for enlivenment and fluidity—inspired me to transpose his work to three-dimensional space. Here, the energy and geometry can come to life even more powerfully.

This series was also inspired by our shared experience of temporal transition: Blake’s life spanned the transition from the Enlightenment to the Industrial Age; I have lived through the transition from the Industrial Age to the Information Age. These discordant shifts fuel our artistic expression.

Blake illustrated the then 124-year-old poem “Paradise Lost” in 1808, when his culture seemed threatened by the encroachments of the Industrial Age. The rebel angel of the 19th century was the mighty mechanical machine, which challenged Blake’s Enlightenment-era God. Blake resisted the influences of industrial materiality. The characters of his Paradise Lost illustrations act out the defining gestures of Milton’s story in weightless bodies. Their gestures appear as lines of force that energize the page.

Two centuries later I have re-set Blake’s “Paradise Lost” illustrations in my constructed mechanistic environments as if they were lost products of the Industrial Age. Mysteriously operative machines augment the gestures of Blake’s characters. I assemble these machines in large part from materials found in the scrap refuge of the fading Industrial Age era, when domestic cultural stability underlay America’s apex of power at the height of its mid-20th century industrial might.

Two centuries later I have re-set Blake’s “Paradise Lost” illustrations in my constructed mechanistic environments as if they were lost products of the Industrial Age. Mysteriously operative machines augment the gestures of Blake’s characters. I assemble these machines in large part from materials found in the scrap refuge of the fading Industrial Age era, when domestic cultural stability underlay America’s apex of power at the height of its mid-20th century industrial might.

The rebel angel of “Industrial Paradise Lost” is the unseen force that directs Blake’s machine-empowered characters: the spirit of the machine itself. Whereas early 20th century Man commanded machines to “make” according to His direction, by the mid-20th century Man commanded machines to “think”. Today the machines, with thinking capacities far exceeding those of the human brain, seem only nominally controlled by their human programmers . As Satan took the form of the serpent, the rebel angel for us now resides in the Digital Mind, which now dares to challenge the omnipotence of its ultimate creator. Having bitten the apple of the Information Age, we now face a future outside the familiar Eden of our past.

– Ted Chapin